Speaking a language is a practical skill, almost like driving a car or cooking. Understandably, most language learners want to start using their target language as soon as possible. When I approach a new language, I feel the urge to say something meaningful from lesson one. However, as a language teacher, I know that for most languages, this is not realistic.

Russian is one of those languages that won’t let you advance quickly. For beginners, and even for intermediate learners, putting Russian words together into a meaningful and grammatically correct sentence is quite a challenge. If you struggle with progressing in Russian further than making a simple, childish sentence, no worries – it’s not you, it’s the language. There are objective reasons why producing a phrase in Russian is so hard. In this series of articles, I’m going to talk about those reasons and show you how to make your Russian studies a little bit easier. The first article is about the Russian case system.

Russian Cases: what do they do

Russian is one of the synthetic languages, and as such, it uses lots and lots of inflections or “endings” to express the relationships between the words in a sentence. In English, direct Subject-Verb-Object word order helps understanding. In Russian, word order is flexible and doesn’t help much. The object can go before the verb, and the subject can easily be the very last word in the sentence. It’s those innumerous endings that show who does what and to whom.

Russian uses the case system to manage relations between words in a sentence. As you might know, Russian has six cases, and each case has a core, general meaning:

- Nominative case is for subjects;

- Accusative case is for direct objects, similar to English “him” in “I saw him”;

- Dative case is for receivers, beneficiaries in the broadest sense, similar to English preposition “to”;

- Genitive case is for possessors, or “being a part of”; in English, the preposition “of” usually does this job;

- Instrumental case is, apparently, for instruments, and is normally used when in English you would use “by” or “with”;

- Prepositional case, also called locative case, is for locations and for announcing the topics of speech, like “about” in “We are talking about …” or “of” in “I’m dreaming of… ”

Мне кот принёс птицу. My cat brought me a bird.

The actual word order in this sentence is: To me the cat brought a bird. The only way to understand that it wasn’t me who brought a bird to a cat, or a cat to a bird, or that it wasn’t the bird who brought the cat to me (imagining that I breed birds of prey, for example) is to check the cases, i.e., the endings of each word. Кот, cat, is written in the way the word is written in the dictionary, so it is in the nominative case, and thus is the subject. Птицу is ‘птица’, bird, in the accusative case, which make it a direct object. Now we know for sure that the cat was the hunter and the bird was the game. Finally, мне is ‘я’, I, is in the dative case — to me. The dative case is for receivers, so it was me who received a nasty present from the cat.

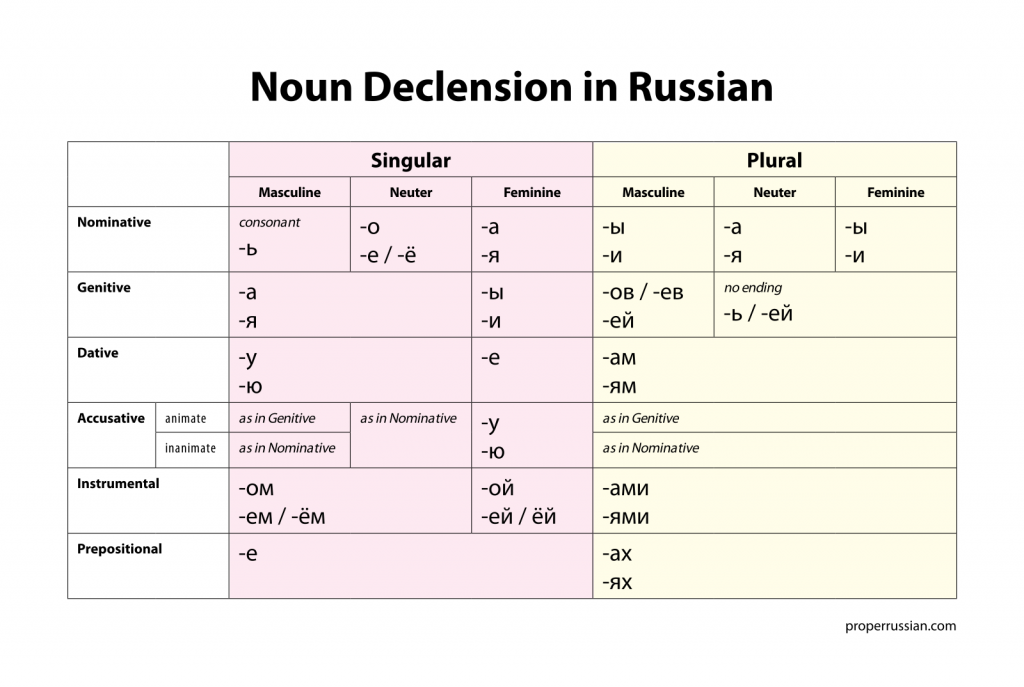

Russian cases pose two big problems for learners. First, one should learn six different forms for each noun (and another six for that word in plural). Almost every noun in Russian has a set of case endings, so every time you add a word in your vocabulary, you should add its 12 variants. Another problem is that a learner has to pick the right case when putting a word into a sentence. “Should I change the word or should it go as it is? If I have to change it, how? What ending should I pick?” If you have been learning Russian for some time, you probably have these questions in your head all of the time.

What is the best way to deal with Russian cases?

As I learned from my teaching experiences, the best way to approach Russian cases is to learn them one by one while keeping the big picture in mind at the same time. The very first step is to understand what cases do and that those endings are to show what a word does in the sentence – is it a subject, object, receiver, possessor, etc.

The next step would be to briefly familiarize yourself with the system of how the endings are organized. The mere fact that there IS a system is very reassuring – where there are patterns, there are ways of memorizing quickly. Russian nouns of the same gender tend to have the same set of endings.

Now that you’ve got an idea about what the Russian case system looks like, you can start learning cases one by one. Do not expect that simply knowing the endings will help you with speaking and building sentences. Think about the grammar table as your mental map. It can tell you where you are and navigate you through the area, but it won’t do the walking or riding for you.

Case Order

In Russian schools, students memorize cases in the following order:

- Именительный | Nominative

- Родительный | Genitive

- Дательный | Dative

- Винительный | Accusative

- Творительный | Instrumental

- Предложный | Prepositional

Most likely, this order was inherited by early Russian linguists from classic Latin text books, and thus has no particular practical sense.

Teachers of Russian as a foreign language suggest learning cases in the following order:

- Nominative

- Prepositional (as locative, for location)

- Accusative

- Genitive

- Dative

- Instrumental

The logic behind this order is that it goes from simplest to most complex and from most frequent to least frequent. Also, this order allows language learners to actively use their vocabulary and expand it gradually. For example, a student can build a simple sentence with a prepositional case knowing a couple hundred words, while dative takes more advanced vocabulary and complex syntax structures.

From my teaching practice, I have learned that the order doesn’t really matter. Most Russian sentences are not limited by one case anyway. Inevitably, learners encounter all the cases very soon, usually as soon as they try to build their first sentence in Russian. However, following the recommended order does make sense. Nobody can learn all of the cases at once, so I suggest to my students to focus on one case at a time while keeping the rest in mind. Simply remember that other cases exist and try to recognize a familiar word in different cases, but do not pay too much attention to them yet.

Working on Cases One by One

Whether you use a textbook or language learning applications, you probably see lessons dedicated to each particular case. Usually those lessons have two types of objectives: 1) to help you understand when to use the case in subject, and 2) to help you memorize and internalize the case endings.

Get the core idea behind each case. Some textbooks are better at explaining the meaning of a case than others. When I opened the official recommendations for teachers of Russian as foreign language and found fourteen (14) meanings of the nominative case, I didn’t know whether I should laugh or cry. Rather than showing the general meaning of the nominative case, the authors of the book decided to get into tiny details and developed a very confusing and illogical hierarchy of semantic nuances that is absolutely not important and totally impractical.

For better understanding when to use this or that case, try to figure out the general, broadest meaning of the case. For example, for the nominative case, it would be “name” labelling, which is most often about the subject of the sentence.

Work through all the examples and exercises. While understanding, which is step one, takes the most abstract thinking, internalizing, step two, takes a thorough focus on details. In order to make putting a word into the right grammatical form your new habit, you have to collect as many examples as possible, and the more, the better. If you feel that the exercises in your textbook are not enough, add extra words to them or try to make a sentence with the case you are learning. If you like Russian songs, take a couple of your favourite songs and try to find nouns in that case there. Or, if you are reading a book, check a couple paragraphs for the words in that case.

Keep calm and practice. You may feel overwhelmed by the amount of endings that you have to take into consideration. Rather than trying to make it perfect right away, keep your focus on the case you are working on at the moment. Do not worry about the mistakes you are making with all the other cases. You are not supposed to start speaking perfect Russian after a few weeks, or even months of learning. You’ll work those cases out one by one. You’ll process lots and lots of sentences in Russian by reading, listening, writing, and speaking, and eventually, you’ll stop thinking about what ending to add to each noun, because you’ll just know it.

Photo by Adrian Sampson